“Take the first left turn. A little further down, you will see the fauji’s photo on a black pillar. That is his house.” An elderly bicycle mechanic in Ramgarh Sardaran points towards a curve on the periphery. People in the village refer to Ajay Kumar as either a fauji (soldier) or a martyr.

In the eyes of the government of India, he is neither.

It doesn’t matter that the 23-year-old defended the borders of this country to the last drop of his blood in anti-insurgency operations in Jammu & Kashmir. His old, landless, Dalit parents cannot even dream of a pension, or martyr status for their son. They are not eligible for any benefits under the Ex-Servicemen Contributory Health Scheme, or even the Canteen Stores Department discounts. For, in official records, Ajay Kumar was neither soldier nor martyr.

He was just an Agniveer .

In this village of Ludhiana district, though, the government record carries little weight. A 45-minute drive from Grand Trunk Road, beautiful fields blooming with mustard flowers take you to Ramgarh Sardaran, where the walls seem to have already written their own record. Dotted with hoardings carrying a handsome Ajay’s photos in olive green, they position him in seamless continuity to martyr Bhagat Singh, who, along with his comrades, walked to the gallows over nine decades ago, but is yet to be given the status of martyr by successive governments.

One of the hoardings in the village reads:

Naujwan jad uthde ne

Taan nizaam badal jande ne,

Bhagat Singh ajj vi paida hunde ne,

Bas naam badal jaande ne…

[When the youngsters arise,

The crowns are cast aside.

Bhagat Singh is born with each new day

But under different names the world may say…]

Left: At the entrance to Ajay Kumar’s house, a black pillar bears his photo. Right: A hoarding in the village Ramgarh Sardaran with the verse carried above

Ajay Kumar sacrificed his life in Jammu & Kashmir in January 2024. Inspired by his maternal grandfather Havaldar Piyara Lal, Ajay wanted to join the Indian Army since his childhood. “He started preparation after completing his tenth,” says his father Charanjit Singh.

“But at the time of recruitment he didn’t know the difference between an Agniveer and a soldier,” he says. Now after his martyrdom, not just his family, but youngsters from the villages around also know what it means to be a ‘soldier on contract.’

“Looking at the rough deal given to us, the youngsters stand demoralised,” Anjali Devi, 22, the youngest of Ajay’s six sisters tells us. They know that even after martyrdom, the family of an Agniveer doesn’t get the facilities given to other soldiers.”

She is scathing in her anger and hurt. “They use Agniveers as a shield because even if an Agniveer dies, there is no liability of the government. As if they are lesser mortals.”

The stories of such treatment meted out to Agniveers have dampened the spirits of aspirants in this state known for sending its children to join the army since the days of the British Raj. During World War-I, which concluded in 1918 – 103 years ago – every second soldier in the British Indian Army was from Punjab, which at the time included present-day Haryana and also West Punjab – now in Pakistan. In 1929, there were 86,000 Punjabi soldiers out of a total army strength of 1,39,200.

The same trend continued till a few years ago. Ministry of Defence data placed before Parliament on March 15, 2021, showed that, with 89,000 recruits, Punjab ranks second among states sending soldiers to the Indian Army. (Uttar Pradesh with seven and a half times Punjab’s population, is the first). Punjab contributes 7.7 per cent of all army personnel despite accounting for just 2.3 per cent of India’s total population. UP accounts for 14.5 per cent of our soldiers though it is home to 16.5 per cent of our population.

A 2022 photo of aspirants for the armed forces. They are lined up at the Physical Academy Lehragaga in Sangrur district before it was shut down after launch of Agniveer two years ago

However, after the launch of the Agniveer Scheme, the situation seems to have changed dramatically on the ground. Army recruitment training centres were commonly seen at both small and big towns all over the state, but most of them have closed down in the past two years as there is a sudden decline in the number of aspirants.

Surinder Singh has shut down his ‘Physical Academy,’ an armed forces recruitment training centre that he ran in Lehragaga town in Sangrur district for almost a decade. He told PARI that every year, the academy used to provide physical training to around a thousand youngsters from Patiala, Sangrur, Barnala, Fatehgarh Sahib and Mansa districts in several batches. But the year the Agniveer scheme was launched, the number of queries from aspirants came down to just 50. “We were not able to even meet the expenses, so we closed down the centre,” he says regretfully.

Between the launch of his centre in 2011 and its closure in late 2022, “about 1,400 to 1,500 youngsters we trained here joined the Indian armed forces,” he says.

Surinder Singh says the situation with other physical training centres in Punjab, Rajasthan and Haryana is no different. “Around 80 per cent of them have shut down,” he says. And the 20 per cent which are still running have shifted their focus to police and paramilitary forces’ recruitment.

“If earlier 50 to 100 youngsters from a village were interested in joining the armed forces, that number is now between two and five. Such is the massive impact the Agniveer Scheme has had,” he says.

Karamjit Singh, who once ran the New Sainik Public Academy in Nabha town of Patiala district, tells us that in 2023, 60 students cleared the written examination for the armed forces. However, only a few of them came for physical training because the implications of the new scheme had become clearer to them. Eventually, the academy was closed down.

Across the state army recruitment training centres like this one in Sangrur, have closed down in the past two years as there is a sudden decline in the number of armed forces aspirants

Jagsir Garg from village Alipur Khalsa in Sangrur district was among those students who cleared the written examination but didn’t go for the physical test. Reason? “My parents said that there was no need to risk my life just for a four-year job. In case of a mishap, the family doesn’t get anything. There were many in my batch in the academy who didn’t go for the physical test despite clearing the written examination,” he says. Jagsir is now into the business of buying and selling used motorbikes.

Because of a long-standing tradition of sending children to the armed forces, recruitment academies have a presence in all big cities and small towns of Punjab. Today, as Surinder Singh pointed out, most of these have either shut down or diversified into police recruitment training. First, these centres were hit by a ban on recruitment between March 2020 and March 2022. Mainly because of Covid –but also, immediately after, due to a question paper leak.

Then the government came up with the Agnipath Scheme. It was announced as an ‘attractive’ recruitment scheme on June 14, 2022 by the union Cabinet. Under this, youth would be recruited in the army for just four years instead of the regular cadre where minimum service is of 15 years.

The government has tom-tommed the scheme as one which would “usher in a new era in the Human Resource policy of the three services.” As PARI’s reporters have pointed out in earlier stories: till 2020, average annual recruitment to the armed forces stood at around 61,000. Under the Agnipath Scheme, this would fall to around 46,000 youngsters.

The fall marked the death of the dream of a lifelong career in the army that was so important to many rural youth. Now on, they would have just a four-year tenure after which only one-fourth of them would be absorbed into the army’s regular cadre.

Apart from the respect the armed forces command in rural society, favourable employment conditions were the main motivation behind the enthusiasm of Punjabis to join the forces, says Dr. Umrao Singh, former head of the Department of Defence and Strategic Studies, Punjabi University, Patiala.

Because of a long-standing tradition of sending children to the armed forces, recruitment academies have always had a presence in big cities and small towns of Punjab

“Following the roll out of the Agniveer scheme, the respect which this job used to once command, has taken a hit. They are now called theke wale fauji – or soldiers on contract. The respect factor thus undermined, the number of aspirants has come down drastically. After the launch of Agniveer, there was a sudden jump in the number of youngsters going abroad. But now curtains have come down on that option too because of soured ties with Canada. Already deep in agrarian crisis, Punjab’s rural society seems to be staring at a catastrophe,” says Dr. Singh.

An overwhelming majority of the recruits came from either farming families or were landless Dalits. As Yadwinder Singh, who prepares army aspirants for the written examination in Rangrial village in Mansa district points out: “Earlier, there used to be a lot of enthusiasm even among boys from families owning five-seven acres of land, but now we hardly get any aspirants from a farming background. Now youngsters mainly from Dalit families, who don’t have any other option, are the only ones showing interest.”

Ajay Kumar belonged to such a landless Dalit family. “To realise his dream, he worked as a daily wager for many years and his mother would do odd jobs from cleaning cattle sheds of landlords to MGNREGA works,” says his father Charanjit Singh. “And what did we get in return? Money? The money will vanish into thin air.” He is referring to the money from insurance, and not compensation since Ajay was entitled to none.

Charanjit points at all that remains: a carefully placed black army trunk with slanting letters in white paint reading, ‘Agniveer Ajay Kumar.’ The three letters seem to tell a tale of broken dreams, not just those of Ajay, but of an entire generation of youngsters in Punjab.

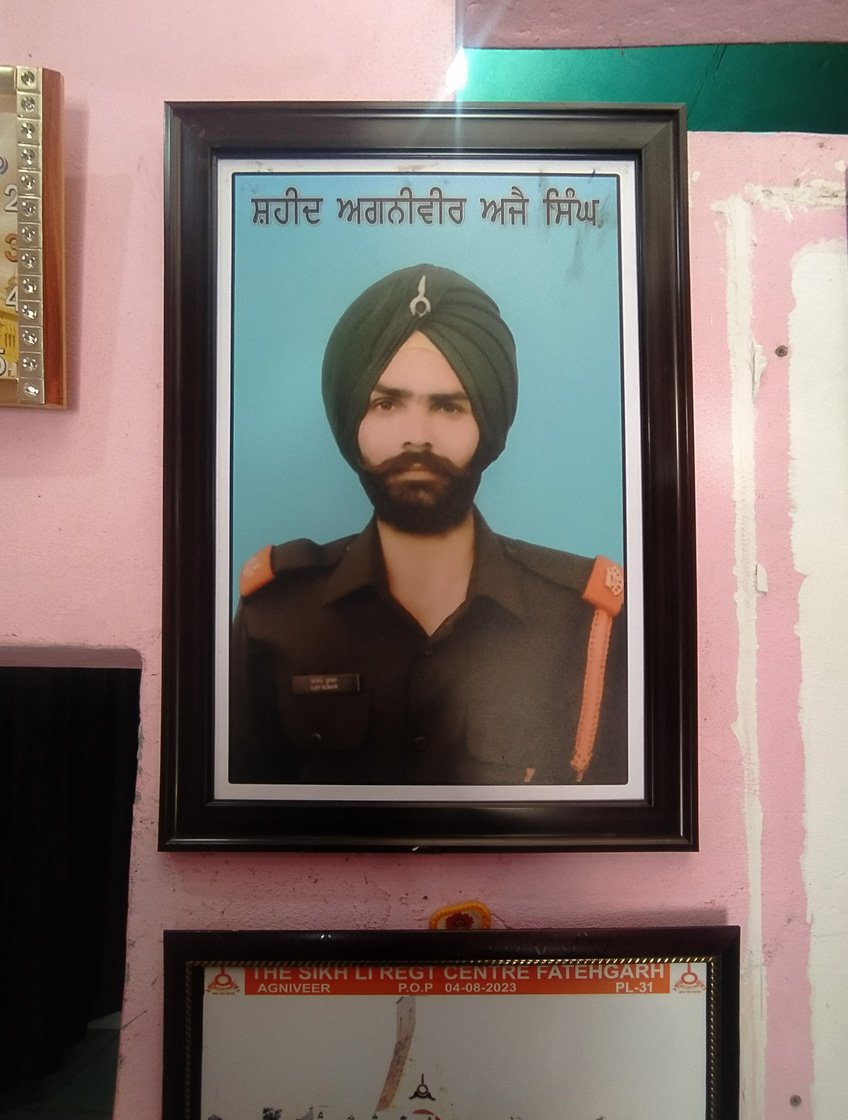

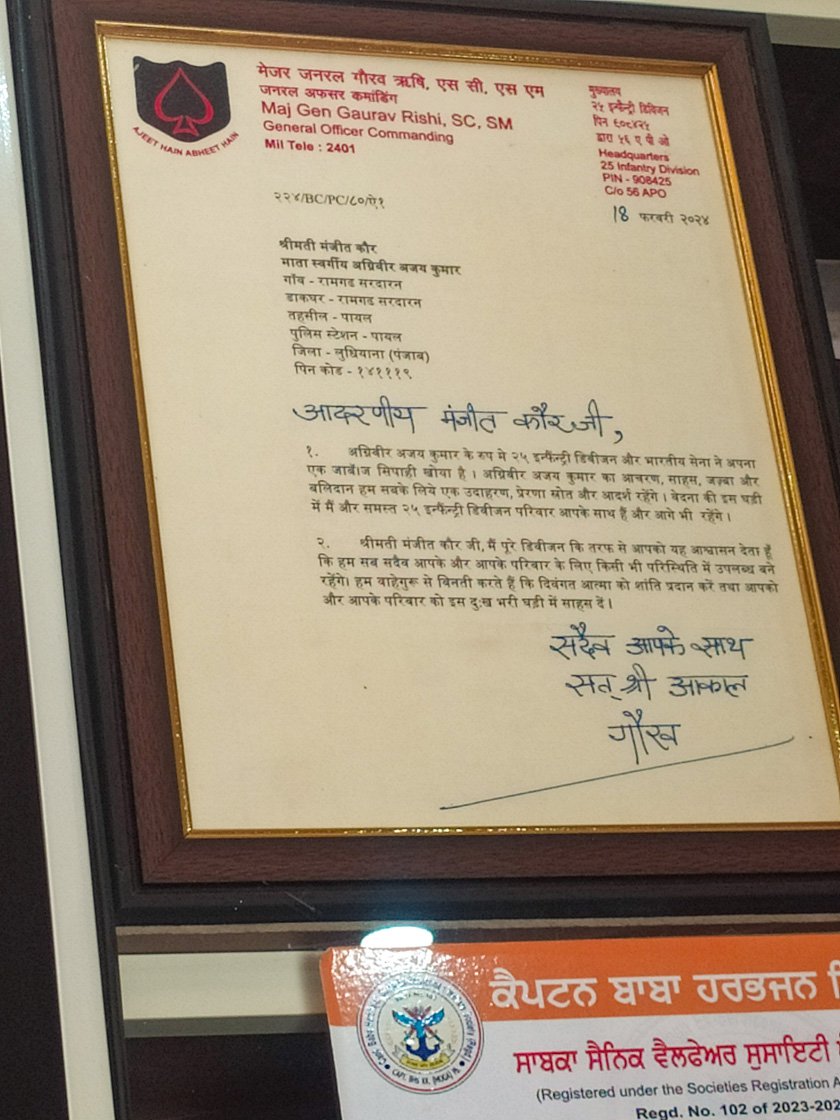

Left: Agniveer Ajay Kumar’s portrait in his house. Right: A condolence message sent to the family by Major General Gaurav Rishi, General Officer Commanding of the 25th Infantry Division to which Ajay belonged

Left: Agniveer Ajay Kumar’s trunk placed in his room. Right: His parents, Charanjit Singh and Manjeet Kaur. A flex board in the background carries a verse on the motherland and sacrifice (see text below)

A newly-constructed room in Ajay’s home appears to have merged with the past too soon, filled with memories of the only son, the only brother among six sisters – two of them unmarried. His ironed uniform, his carefully placed turban, his polished shoes and his framed photos now remain.

Amid the long silences marking the conversation, we ask an obvious question of Ajay’s father: would he still suggest joining the army to other boys from the village? “Why would I do that? Mine has gone for nothing. Why should the sons of others meet the same fate?” he asks.

Upon the wall behind him, a flex with Ajay’s photo speaks:

Likh dyo lahu naal amar kahani, vatan di khatir

Kar dyo qurbaan eh jawaani, vatan di khatir

[For the love of the motherland, ink immortal tales with your blood

For the love of the motherland, go sacrifice your youth…]

Lost in a sea of memories, the eyes of Charanjit Singh seem to be asking a question: what will the motherland offer them in return?

Postscript:

On January 24, 2025, another body wrapped in the tricolour reached a small farmer's house in Aklia village of Punjab's Mansa district. That was of 24-year-old Lovepreet Singh, the third Agniveer from Punjab in the last 15 months to lay down his life while defending the borders of his country.

All of them died in Kashmir. First among them was Agniveer Amritpal Singh who lost his life in October 2023. He was followed by Ajay Kumar in January 2024, mentined in the story above. Like Ajay Kumar's family, Lovepreet's father Beant Singh is left only with memories.

"Lovepreet got a new watch delivered at home; he was looking forward to wearing it upon his return. But that won't happen now," cried Beant, who broke down while talking to media persons. Time seems to have stopped for another family. However, with every fallen young man, the cry for honour and fairness for Agniveers gets louder each day in Punjab.